What is that?

Table of Contents

“one of the largest as well as the commonest sort of oak in Nipal, where it attains the most gigantic size. The wood is exceedingly like the English oak in colour, and most probably equals it in other respects, but the mountaineers do not esteem it much, owing as they say to its speedy decay; a circumstance owing no doubt to their employing it in its green state.”

Lithocarpus elegans is a regionally widespread stone oak species native to Singapore. This page seeks to inform you, the reader, of the interesting characteristics, ecological roles and taxonomy of this plant.

Many are surprised to learn that there are Oak-trees in Singapore. This is perhaps because people often think of wavy edged leaves as the distinguishing feature of Oak trees. Although this is characteristic of some English and North American species, it is the exception rather than the rule. In reality, most species have entire margins [8]. The true distinguishing feature of Oak species is the ripe fallen acorn!

Should I eat it?

There are no records of L. elegans acorns being consumed in Singapore, but the acorns are edible. They are rarely eaten and have reportedly been consumed in the past, in times of food shortage and in the absence of better foods. The acorns are not particularly palatable as the seeds are rich in tannins, making them bitter. The tannins can be removed by soaking the acorns in water and disposing the water bath. The fruit is usually cooked but can also be eaten raw. It may be had whole but is more often dried, ground into a powder and used for thickening stews, with cereals or to make bread [4][14].Well, what else is it good for?

Like the fruits, the L. elegans bark is rich in tannins and can be used as a dye and as a preservative. The tree has yellow-brown sapwood. This wood is used in Indonesia to construct fence posts, mining props, shingles, boat building, and for making tool handles [6].Although it is not a common sight in Singapore's parks and gardens, in other countries L. elegans is considered an ornamental plant and is utilised for streetscaping and landscaping purposes [4]. Indeed, there is potential to employ L. elegans to beautify the Singaporean "City in a Garden". It may arguably even be better suited in fact, as a native tree, than the exotic Albizia saman, Swietenia macrophylla, Khaya senegalensis, Tabebuia rosea, and Xanthostemon chrysanthus species each with over 10,000 individuals that dominate the Singaporean landscape [19].

Where can I find it?

Ecology

Lithocarpus elegans can be found in various habitats from mixed dipterocarp forests to lower montane forests and up to 1500 m altitude. The tree is able to thrive on a variety of soils and is tolerant of neutral to acidic pH levels [4]. As with all members of the Fagaceae family, the plant is associated with fungi by means of extensive ectotrophic mycorrhizal connections. Interestingly, it has been hypothesized that the pioneer settlement and rich development of the Oak-family in Southeast Asia, is related to the rich fungal flora in the region [2][4]. |

| Left: Bifid Plushblue, Right: Darky Plushblue. (Photos by CW Gan) |

Species interactions

The tree acts as a refuge for various animals and its nutrient rich fruits are eaten by foraging animals such as pigs, monkeys, squirrels and rats in the forest. Long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in particular have been observed enjoying the fallen fruits of the tree.

The butterflies Darky Plushblue (Flos anneilla anneilla) and Bifid Plushblue (Flos diardi capeta) use the tree as a larval host [10].

Community development

Studies have shown that L. elegans can accelerate community development in degraded sites such as those damaged due to extensive agriculture or practices such as shifting cultivation [24]. In Long Sungai Barang in Indonesia, L. elegans has been indicated as a significant agent in tree regeneration. This is due to a combination of the ability of the tree to grow in degraded sites, regenerate vegetatively, and produce a large number of seeds.

Distribution

Lithocarpus elegans is widely distributed in East and South East Asia. It has been recorded in India, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Java, Borneo, and Sulawesi [6]. In Singapore, the tree is uncommon and critically endangered. Based on the records available at Singapore Botanic Gardens Herbarium (SING) it can be found at Mandai, Upper Pierce Reservoir, Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and in Nee Soon Swamp forest.The regions in which L. elegans is known to occur are indicated on the map. You can zoom in to see the parts of Singapore where the tree has been identified.

When can I find it?

The tree is evergreen, flowering occurs irregularly but has been known to occur at least one a year, usually soon after the dry season. In Malaya and Singapore, flowering occurs in March and April. A distinct spermatic odour is known to emanate from the inflorescence and this plays a role in the insect pollination of the flowers. Fruiting is usually profuse and occurs within 3–6 months of flowering.How is it dispersed?

The fruits are large, heavy and cannot float. Dispersal cannot occur by means of water and beyond the forest margin dispersal is very slow. This is especially interesting given the vast distribution of L. elegans and suggests that the present and historical distribution of the species was significantly influenced by the presence of land in past geological periods.How does it grow?

To germinate successfully, the nuts must be buried in the soil or covered by soil wash. The mode of germination is hypogeal, meaning the fleshy cotyledons of the nut remain underground. Under favourable conditions of high temperatures and humidity, germination may take place within 1–2 weeks after the acorns are shed. Young plants grow successfully in the shade, but older trees do well in the sun [5].When the tree blossoms it hums with insects; attracting bees, beetles and flies for pollination. This is a characteristic of the tropical oak that distinguishes it from the temperate wind-pollinated species [7].

The female flower spike ripens into a fruit spike along which the acorns develop. Young acorns are covered by the developing cupule, which enlarges at a greater rate after pollination. As the fruit swells, the acorn presses outwards from the cup and emerges from it [7].

|

| Left: Lithocarpus elegans seedling, Right: Lithocarpus elegans fruits at various stages of development. (Photos by Reuben Lim) |

How can I identify the species?

This species grows as a tree and can attain a height of up to 30 m tall. It has spirally arranged foliage and can be recognised by its distinctive acorns. The beautiful acorns of this tree usually occur in clusters and serve as its best identifying feature.Species Description

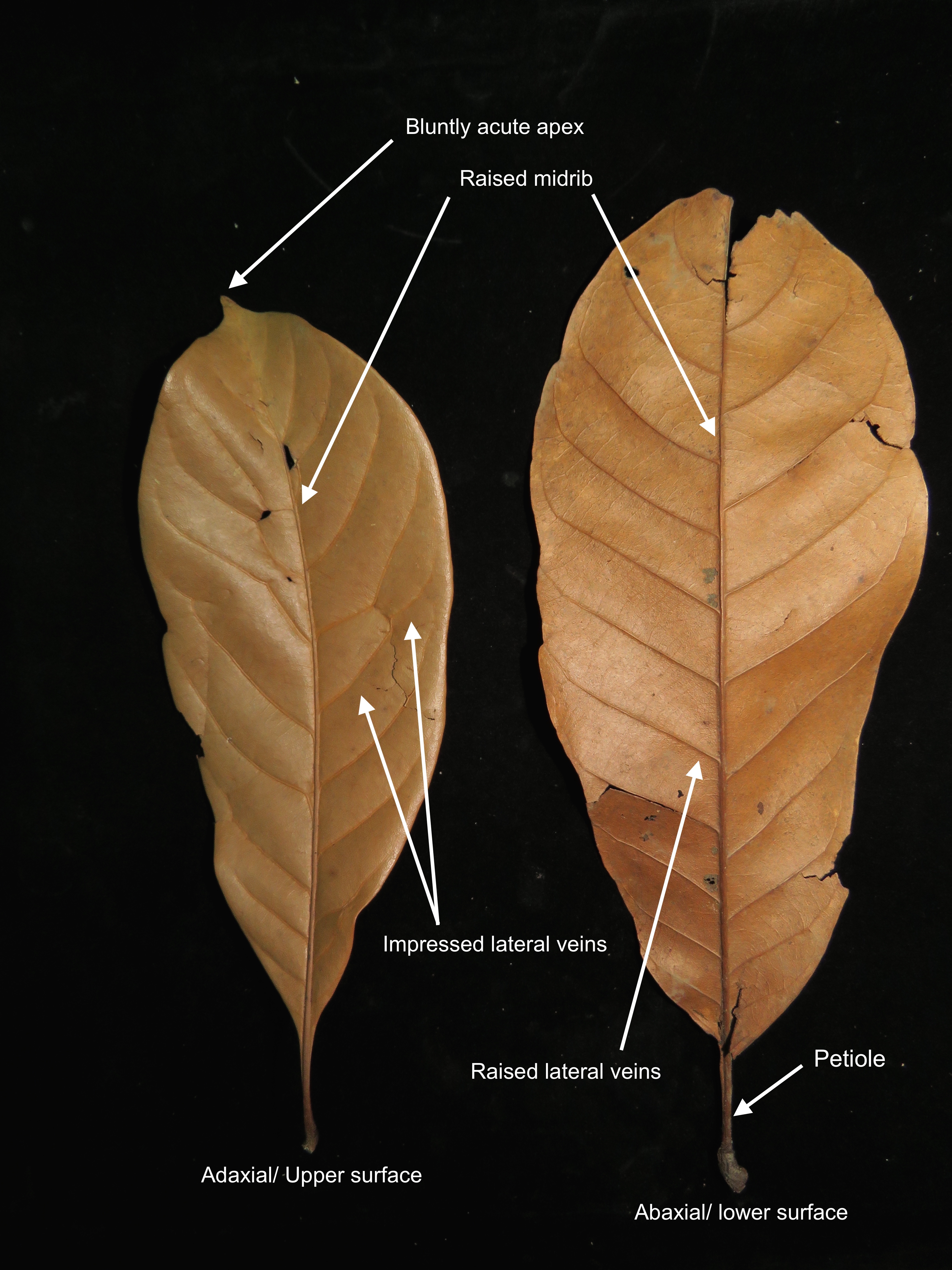

So let's get technical!When a species is described, the author provides a set of diagnostic features which can be used to identify it. The characteristics illustrated through the photos below, as described by the species author Soepadmo, can be used to identify L. elegans [6].

To best understand a plant description it helps to be familiar with some technical terms. So before you dive into the diagnostic features, perhaps you would like to acquaint yourself with this short glossary of botanical terms [11]:

- Abaxial: The side of the organ away from the axis. In the context of leaves, abaxial refers to the lower side of the leaf.

- Acumen: Tapering point of the leaf.

- Adaxial: The side of the organ towards the axis. In the context of leaves, adaxial refers to the upper side of the leaf.

- Androgynous: In refernce to a stalk that bears both male and female parts.

- Axis: The central line of symmetry of the leaf.

- Cupule: Cup-shaped structures that covers the fruit.

- Exserted: Protuding beyond the surrounding parts.

- Fissure: A long, narrow opening due to seperation of plant parts.

- Inflorescences: A flower cluster, or arrangment of flowers on the floral axis.

- Lenticel: A pore in the stem through which gaseous exchange occurs.

- Midrib: The middle and principal vein of the leaf.

- Ovoid/ oviform/ ovoidal: Egg-shaped.

- Rachis: The axis of a compound leaf or an inflorescence.

- Revolute: Rolled downwards at the margin.

- Scales: A flat outgrowth on any surface.

- Sessile: Not stalked.

- Globular/ Globose/ Subglobose: Spherical or globe shaped.

- Veins: Vascular tissue (vessels) in a leaf.

|

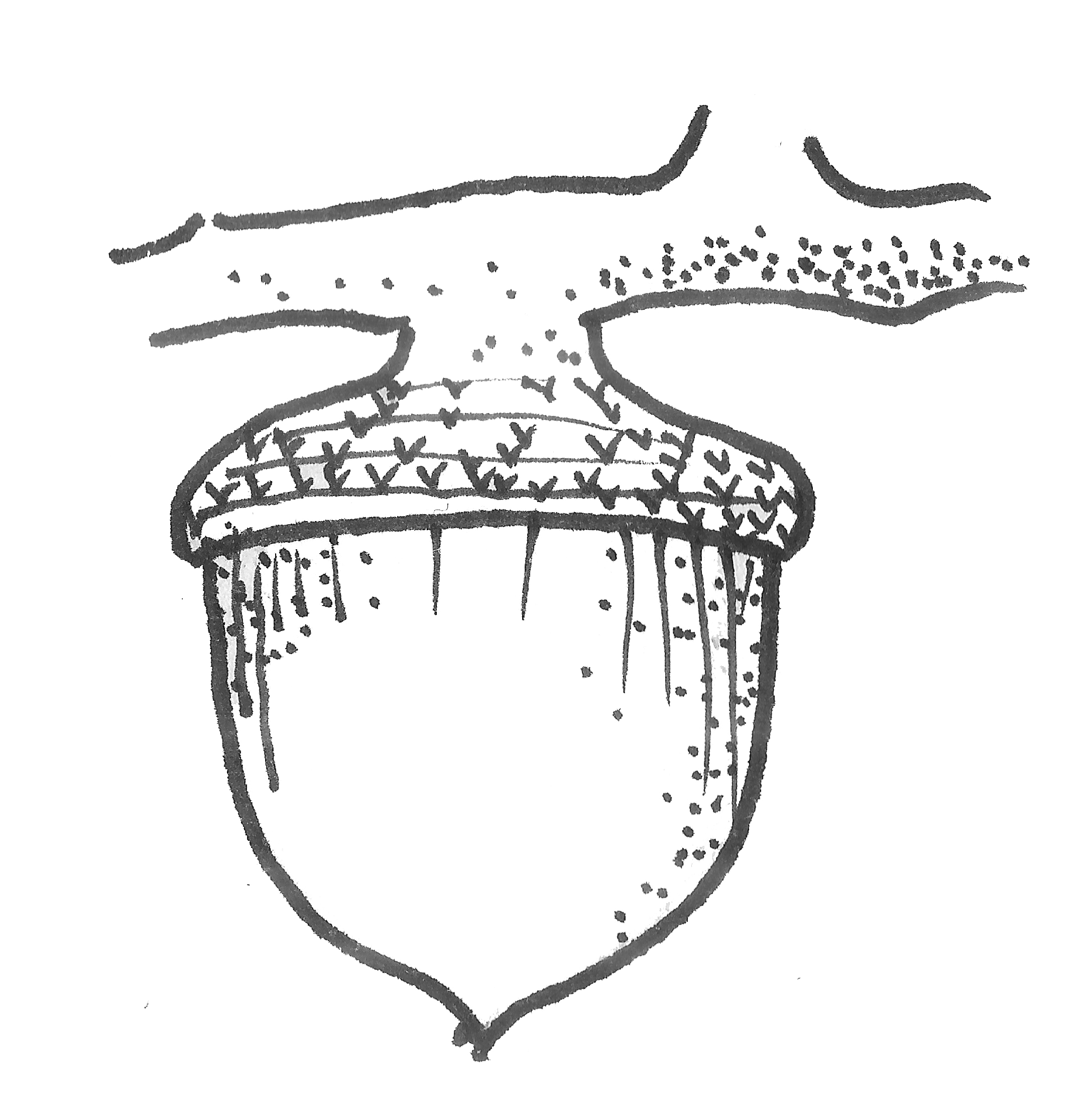

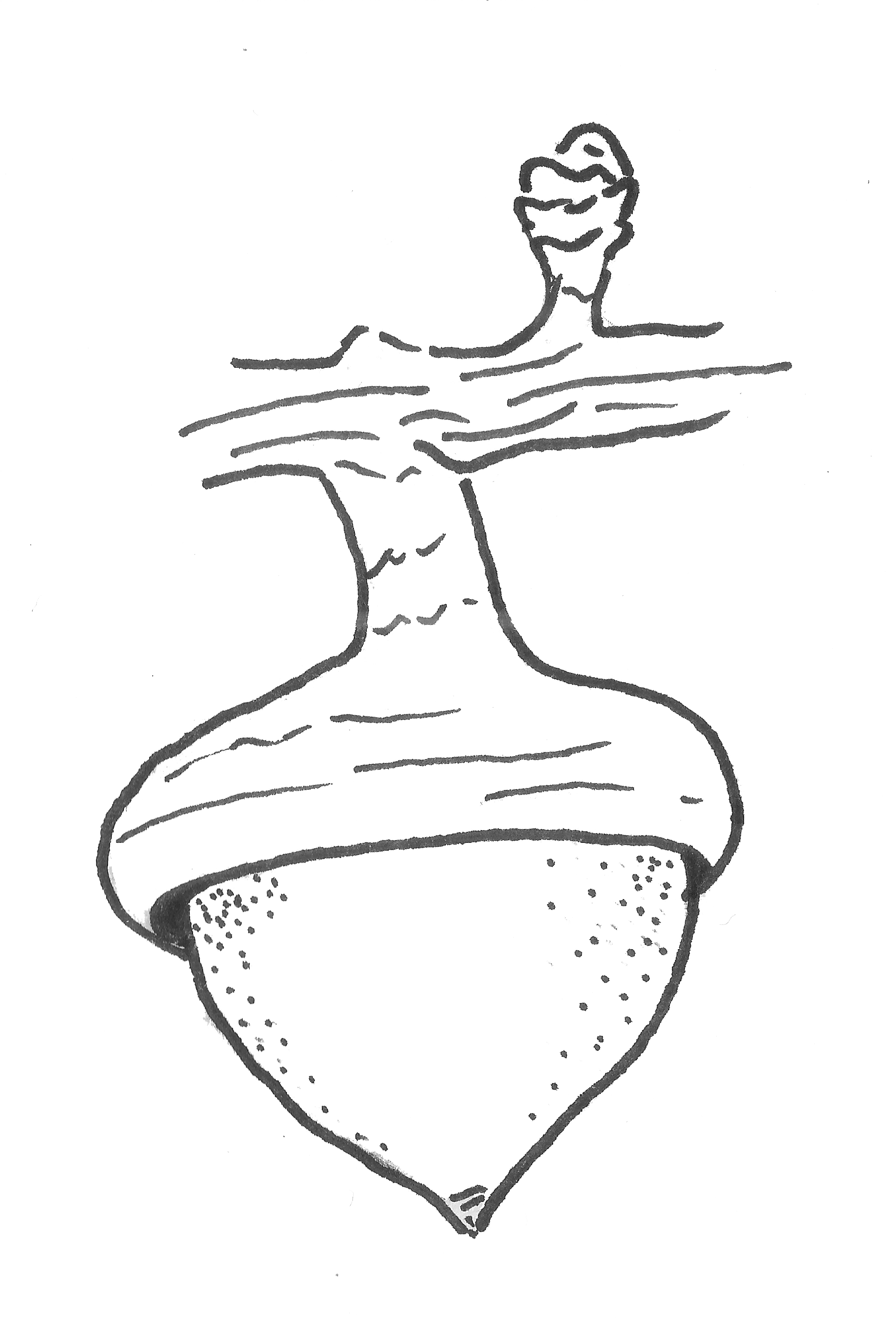

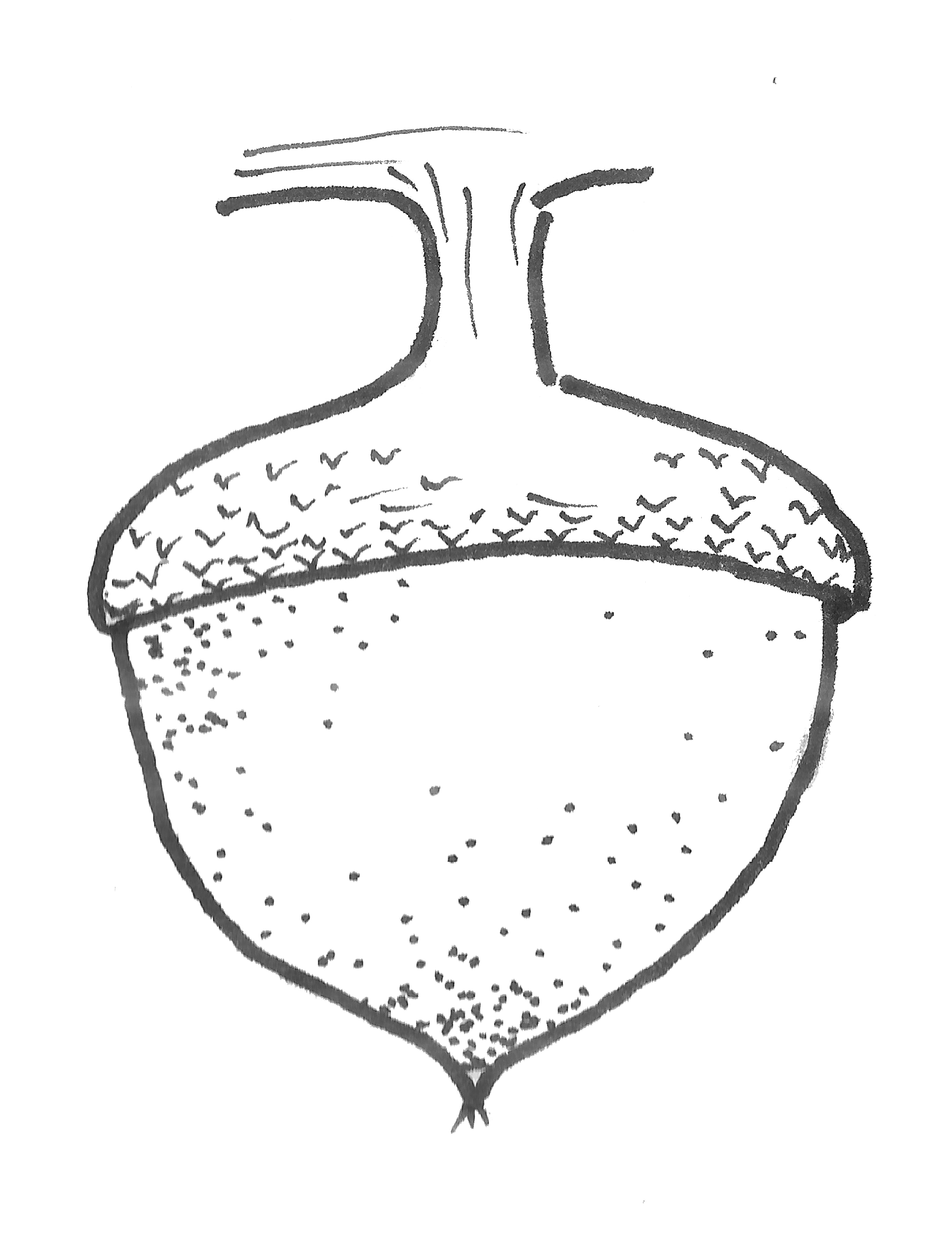

| The cup-shaped cupules occur in clusters of 3–7 or are rarely solitary along the rachis, they may be sessile or with stalk. The thin woody cupule has distinctive scales set in regular lines. The acorns are ovoid or depressed ovoid to subglobose, and for most part exserted from the cupule. The acorn base is flat, apex rounded and the scar flat or concave. (Left: Photo by Reuben Lim, Right: Photo by Srishti Arora) |

|

| Lithocarpus elegans' inflorescences are rigid. The inflorescences can be male, female, androgynous or mixed. In an androgynous inflorescence the male flowers are situated along the upper part and the female flowers along the lower part of the rachis. In a mixed inflorescence, on the other hand, the male and female flowers are alternately arranged along the rachis. Male inflorescences are 10–20 cm long; Male flowers are solitary but closely arranged along the rachis (left). The mixed inflorescences are 12–20 cm long. The female flowers are in clusters of (2–)3–7(–10) along the rachis (right). (Photos by Cerlin Ng) |

|

| The leaves are narrowly to broadly obovate or elliptic. Dimensions range from (9–)12–17(–21) × 3–6(–8) cm. The margin is revolute. The apex is bluntly acute or acuminate; the acumen can be 10 – 20 mm long. The midrib is raised on both upper and lower leaf surfaces. The thin lateral veins in pairs of 11–18 are impressed or flat on the adaxial surface and raised below. The petiole can be 7–15 mm long. (Photo by Reuben Lim) |

|

| The leaves are spirally arranged, with an entire margin. (Photo by Louise Neo) |

|

| The outer bark is greyish brown, deeply fissured and lenticellate. (Photo by Yi Shuen (permission pending)) |

|

| The tree can grow up to 30 m tall with 70 cm diameter at breast height. (Photo by Srishti Arora) |

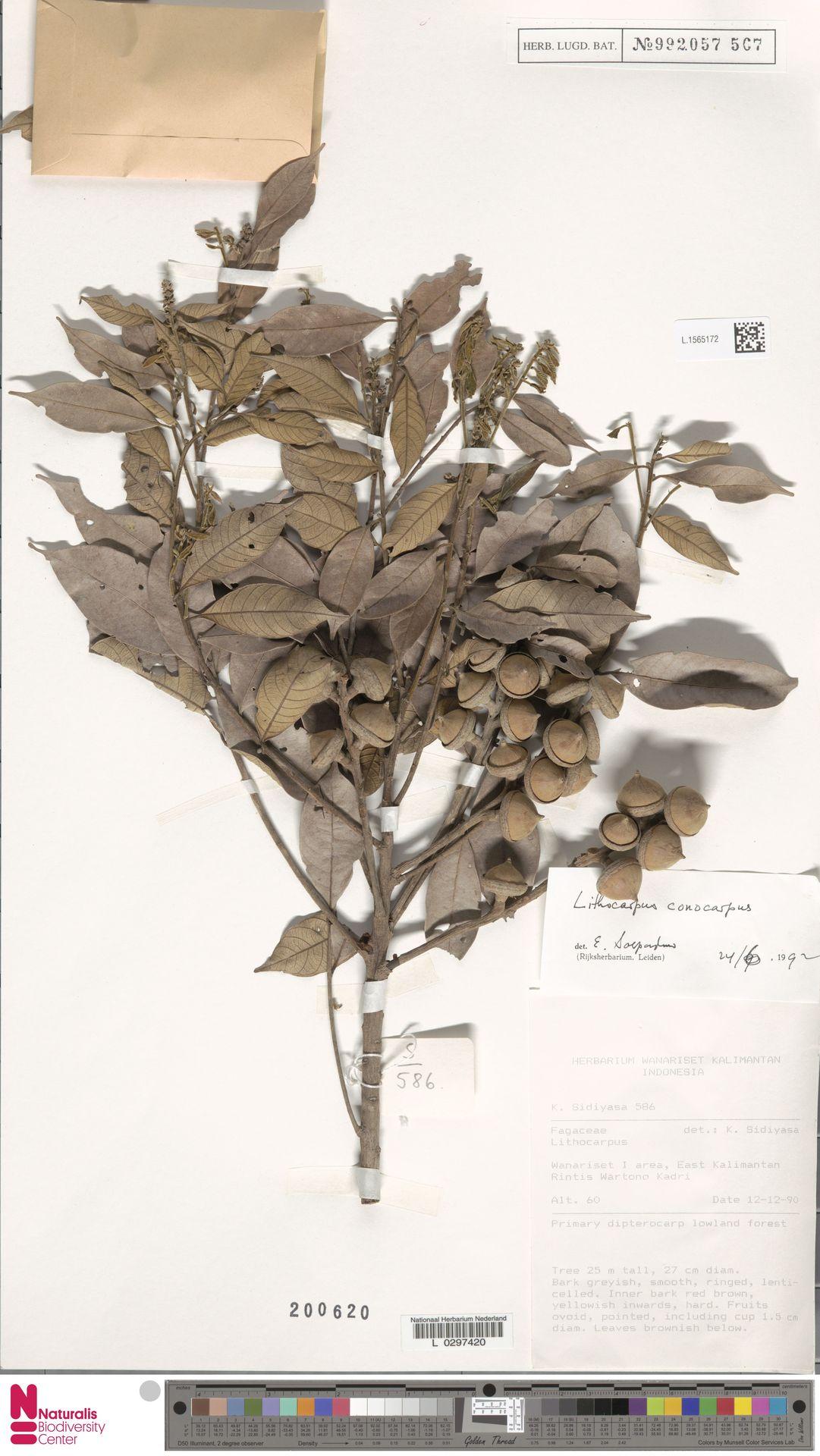

Other Lithocarpus species in Singapore

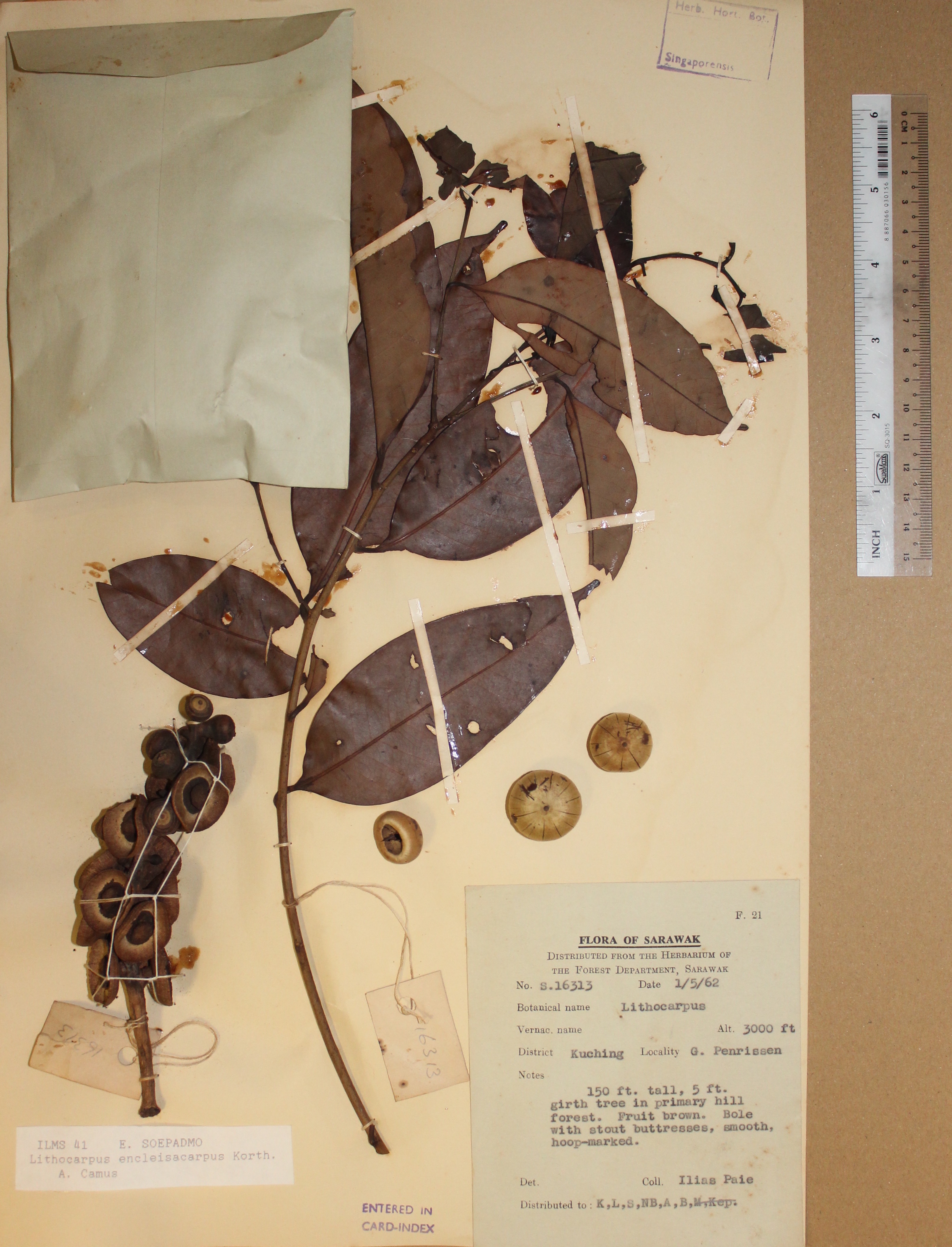

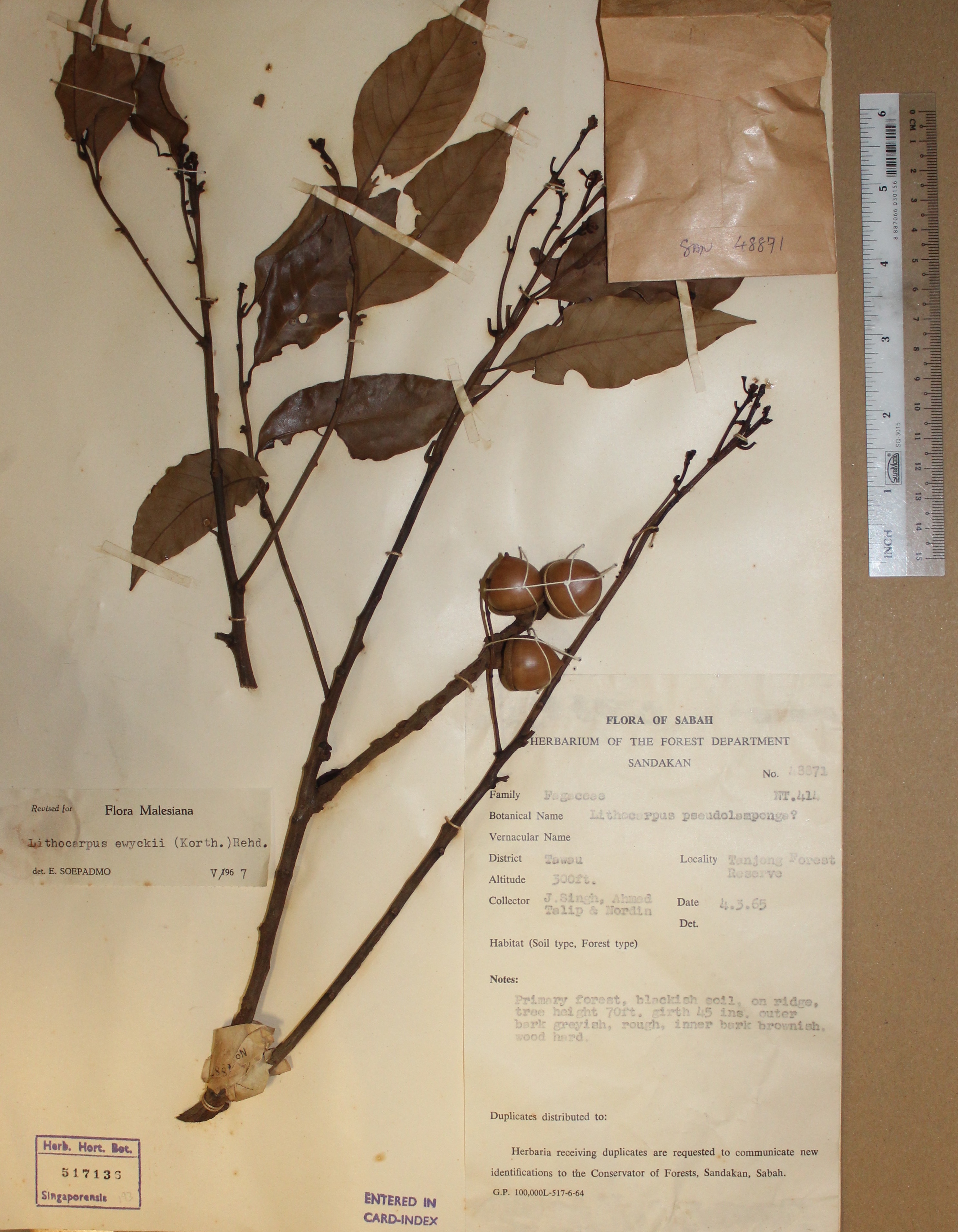

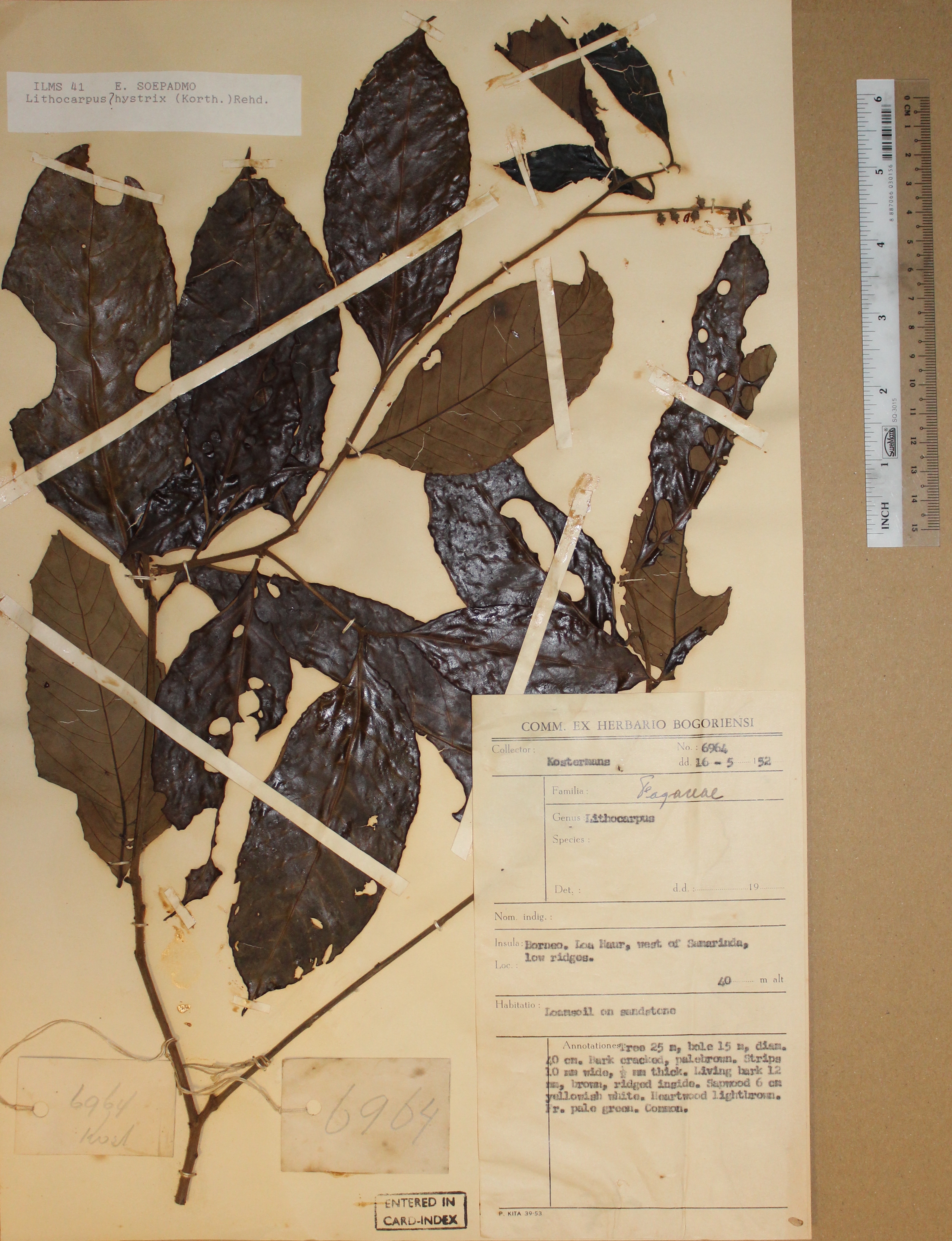

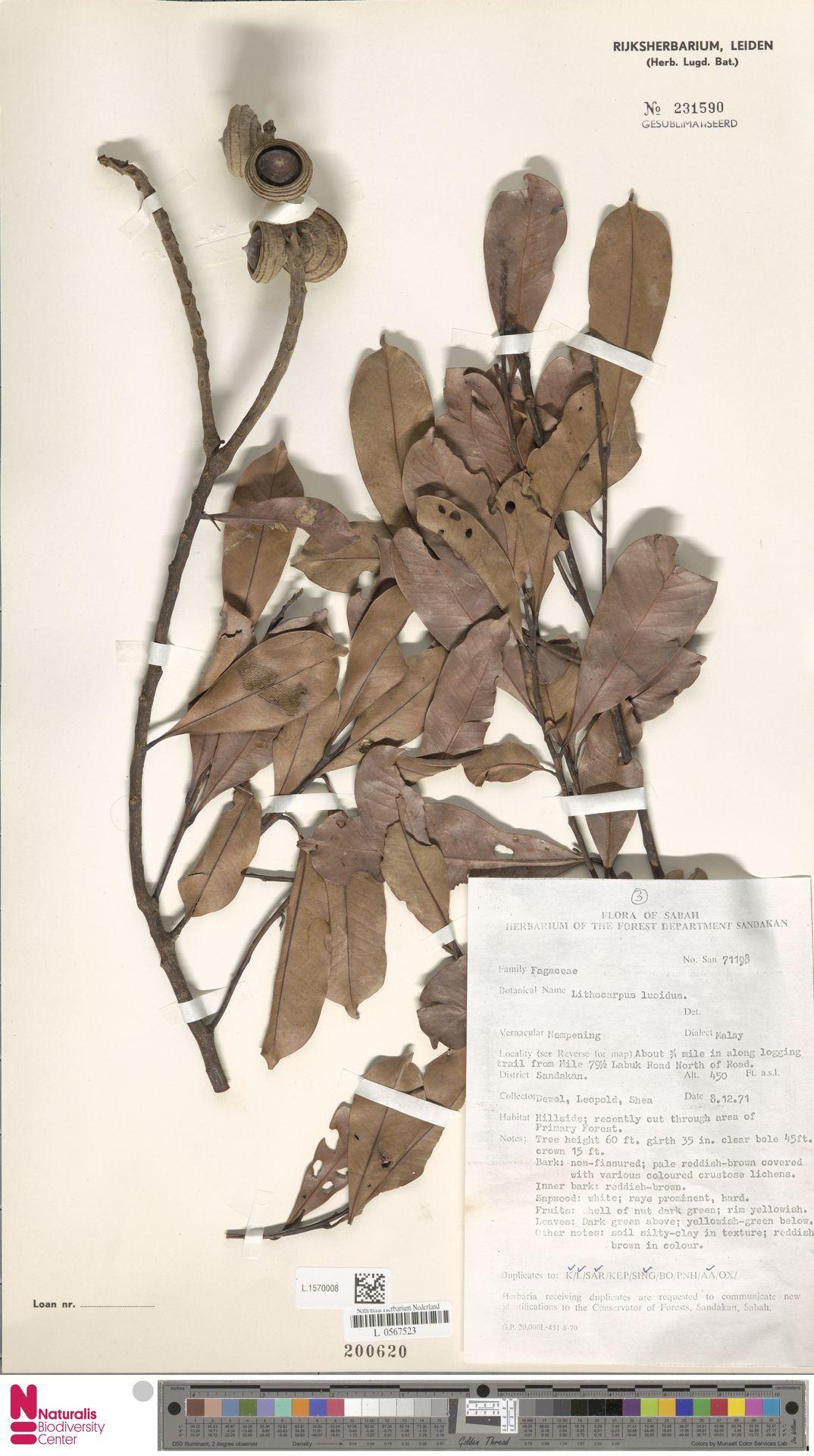

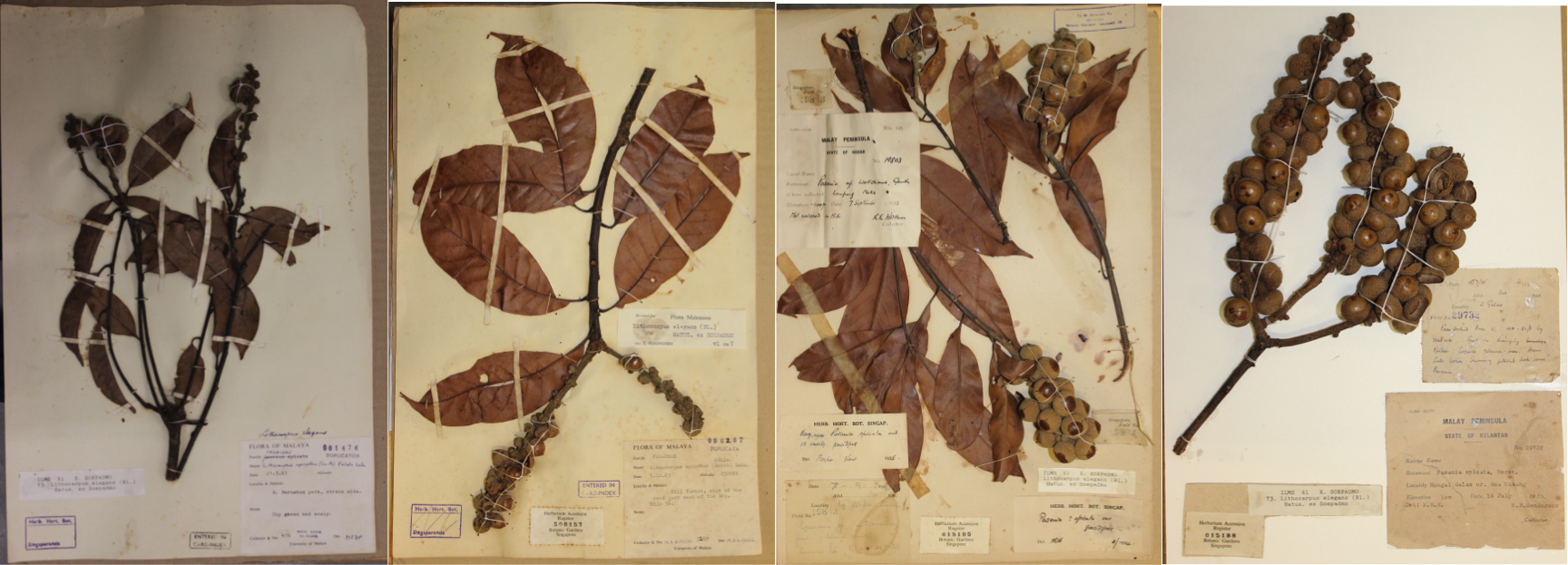

It should be noted however that it can be difficult to identify this species based on vegetative material alone due to its similarity to other Lithocarpus species. The issue however is not particularly relevant to Singapore as Lithocarpus elegans is one of only thirteen species of Lithocarpus that occur here. Of these, only 10 are extant and one among them is a cultivated species according to the Checklist of Total Vascular Plant Flora of Singapore [8].Herbarium Sheet Specimens in a herbarium are dried, preserved, mounted on stiff sheets and labelled with relevant data. Labels usually include information such as date and place of collection, geographic co-ordinates, plant description, altitude and habitat description. The specimens below were all determined by the Lithocarpus expert, E. Soepadmo. |

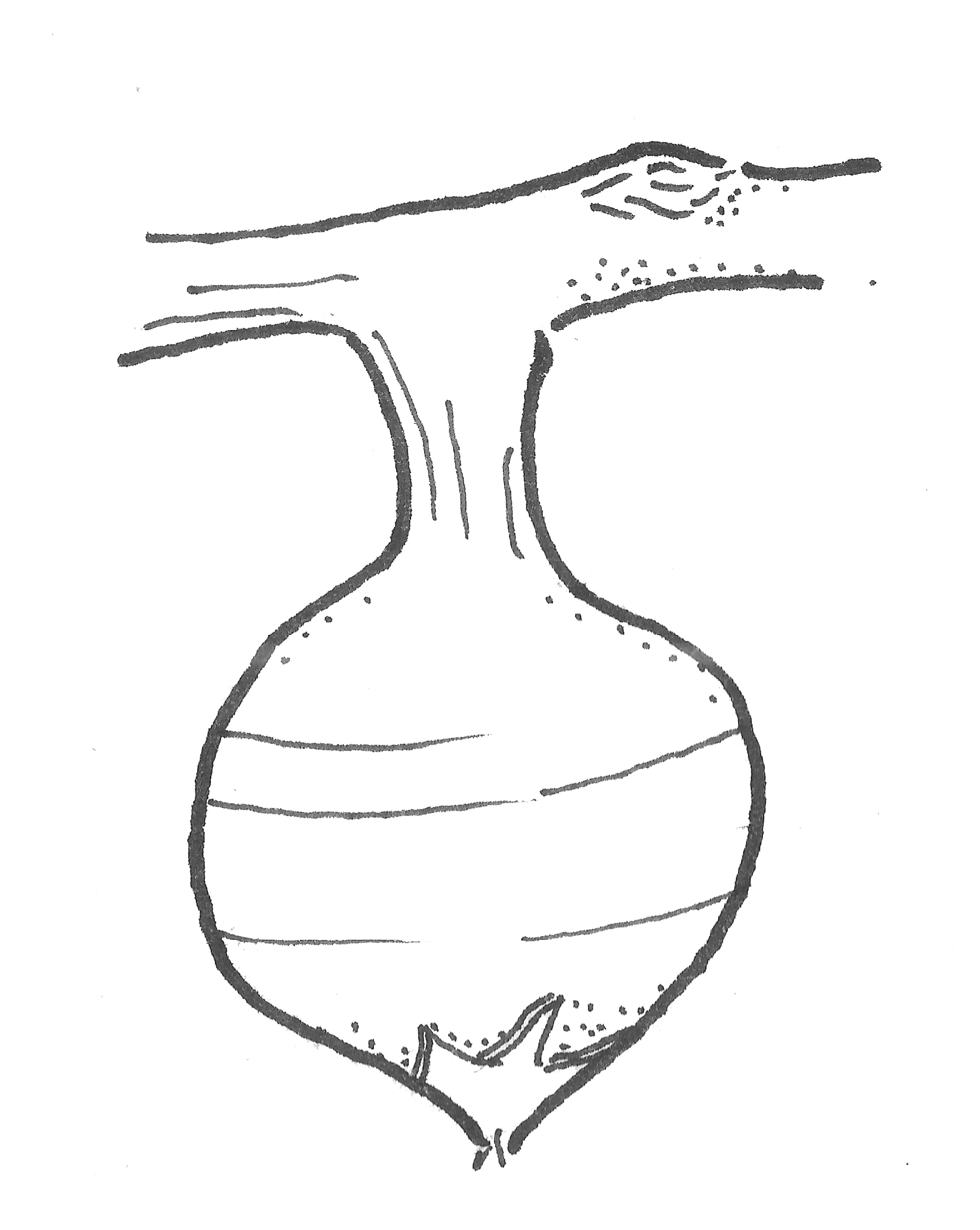

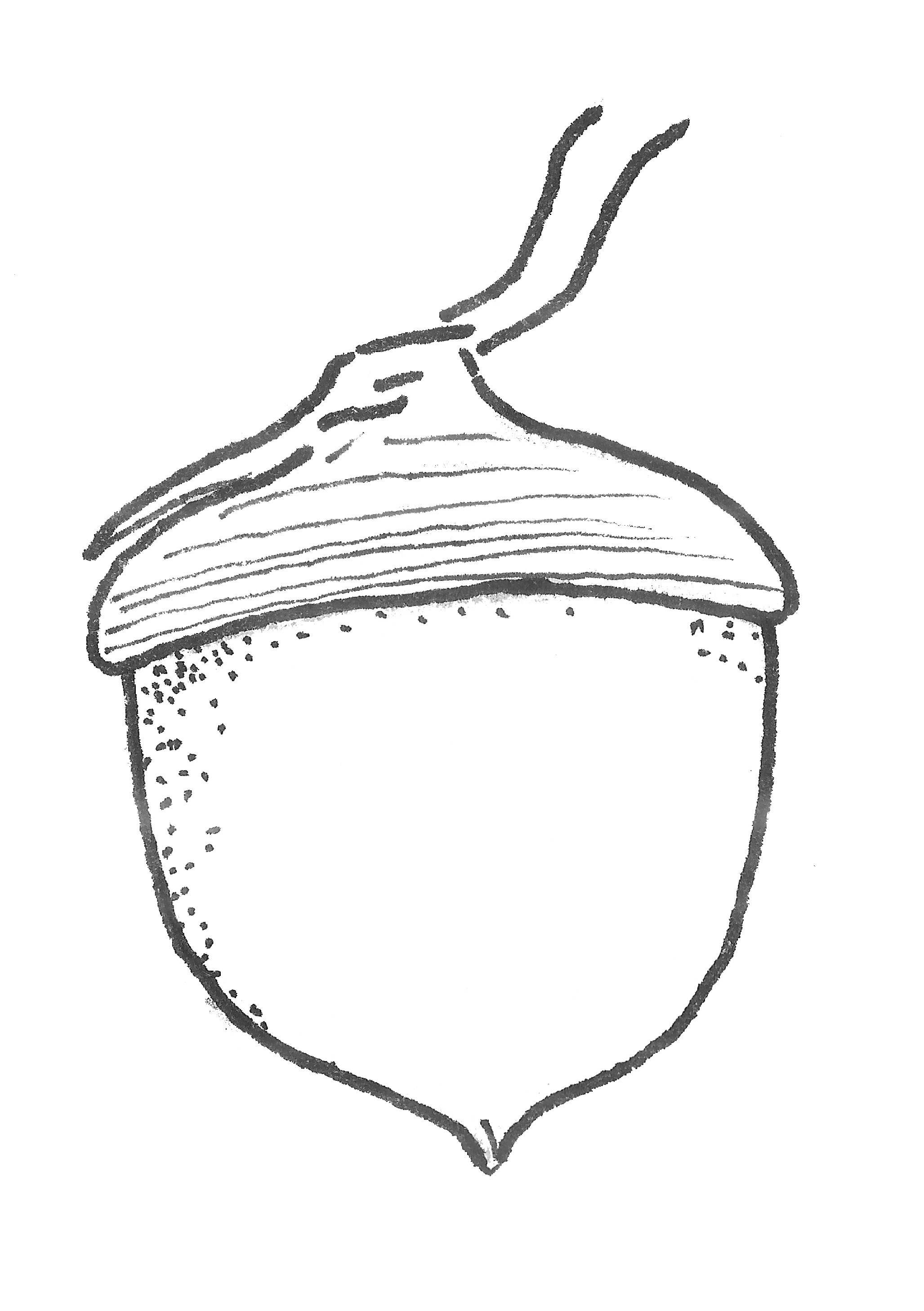

Characteristic Acorn Acorn: Oak (Lithocarpus and Quercus) fruits are known as acorns. The acorns may be solitary along the rachis (i.e. fruiting stalk) or in clusters. Cupule: The cupule is an accessory woody structure that protects the fruit proper. It is usually cup shaped. The cupule may extend from the fruiting stem with a stalk or without one (i.e be sessile). The cupule is rarely glabrous (i.e smooth or free from hair), and is usually denticulate (i.e. finely toothed), scaly, spiny or lamellate. Lamellae: Refers to the distinct concentric circular layers visible on the cupule. Fruit: The indehiscent nuts (i.e. they do not split open on drying) range from being rounded to angular in cross section. The base of the fruit is flat. |

Information about Lithocarpus species Of the 12 species apart from L. elegans known to occur in Singapore, L. cyclophorus and L. gracilis are now extinct and L. rassa is an exotic, cultivated species. The remaining extant native species are detailed below. |

||||

Lithocarpus bennettii (Bennett's Oak)

|

The cupule covers less than half the fruit andmost of the acorn is exserted. It is glabrousbut for the simple hairy apex. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus bennettii thrives on well-drained soils of primary heath and swamp forests. It is found locally, in the Nee Soon Swamp forest. Interesting Note: Though it is presently not cultivated in Singapore, the tree has potential uses in landscaping of parks and gardens. Its timber can be used. |

||||

Lithocarpus cantleyanus (Cantley's Oak)

|

The cupule is cup shaped with a c. 5–7 mm long stalk, densely hairy and has slightly distinct lamellae (5–9) with entire or denticulate edges. The cupule covers less than half the fruit and most of the acorn is exserted. It is glabrous. The fruit base is rounded and the apex is abruptly acute. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus cantleyanus thrives on clay soils of primary forests. The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species is named for a superintendent of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Nathaniel Cantley. |

||||

Lithocarpus conocarpus (Singapore Oak)

|

The cupule is cup shaped with a c. 3–8 mm long stalk, densely hairy and has slightly distinct lamellae (5–6) with denticulate edges. The cupule covers up to half the fruit and most of the acorn is exserted. The fruit is hairy. The fruit base is rounded and the apex is abruptly acute. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus conocarpus thrives on clay-rich soils of primary forests. The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species was once quite common in Singapore, hence its common name — Singapore Oak. |

||||

Lithocarpus encleisacarpus (Covered Oak)

|

The cupule covers most of the acorn, the exserted fruit is velvety. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus encleisacarpus is found in primary and lower montane forests. Interesting Note: The species can be recognized from its silky acorns covered by the thin cup with distinct rings. |

||||

Lithocarpus ewyckii (Ewijk's Oak)

|

The cupule is cup shaped, covering less than half the fruit with a c. 5–10 mm long stalk, sparsely hairy and has slightly distinct lamellae (6–7) with entire edges. Most of the ovoid fruit is exserted with a rounded base and abruptly acute apex. |

Conservation status: An endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus ewyckii found on sandy loam and clay soils in primary and lower montane forests. The tree is cultivated in Singapore. |

||||

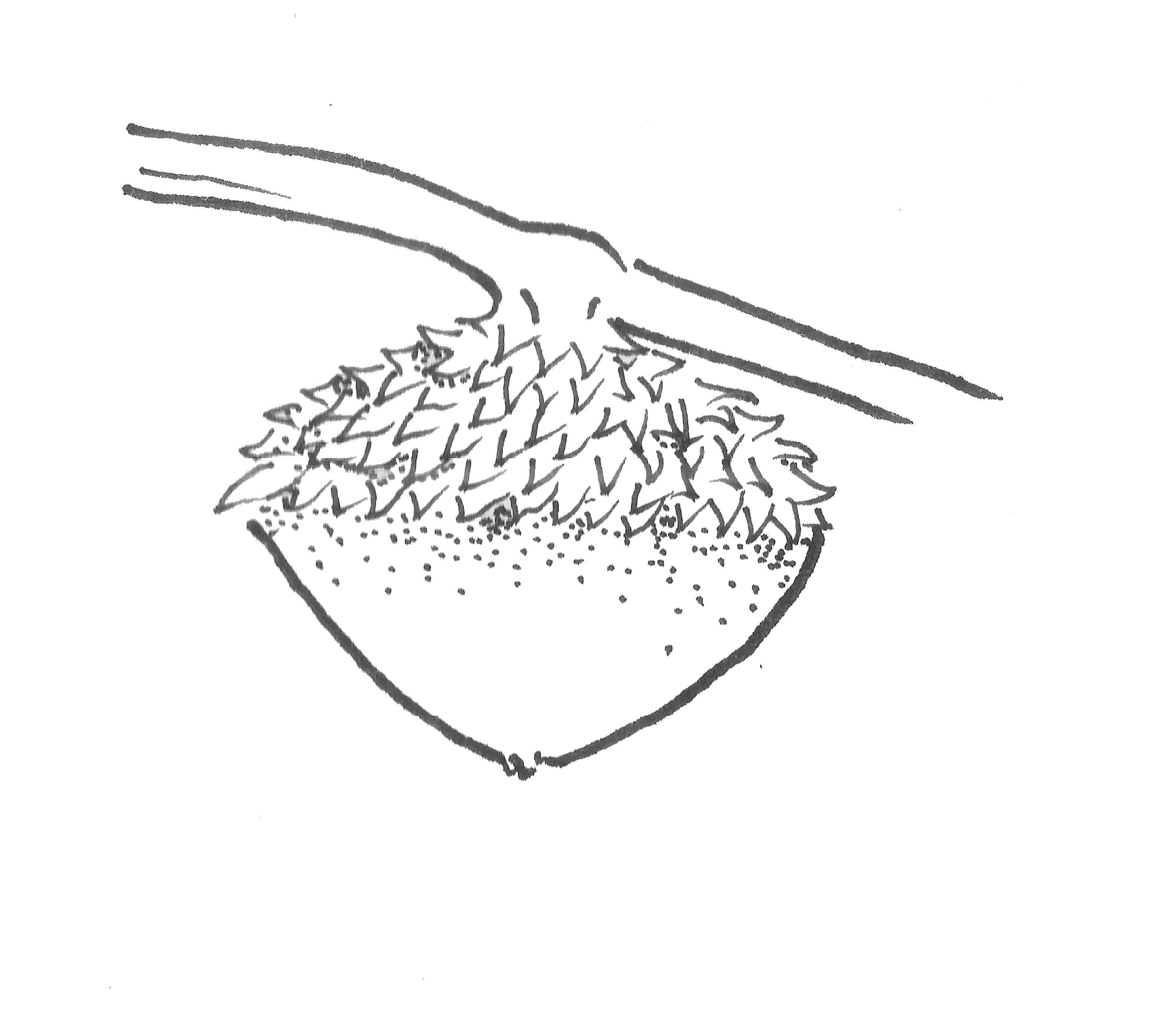

Lithocarpus hystrix (Porcupine Oak)

|

The cupule is saucer shaped, covering less than half the fruit, irregularly set with slender prickle like appendages. Most of the ovoid or conical glabrous fruit is exserted with a rounded base and abruptly acute apex. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus hystrix found on sandy-clay soils in primary and lower montane forests. The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species is named for the slender prickles that cover its cupule. |

||||

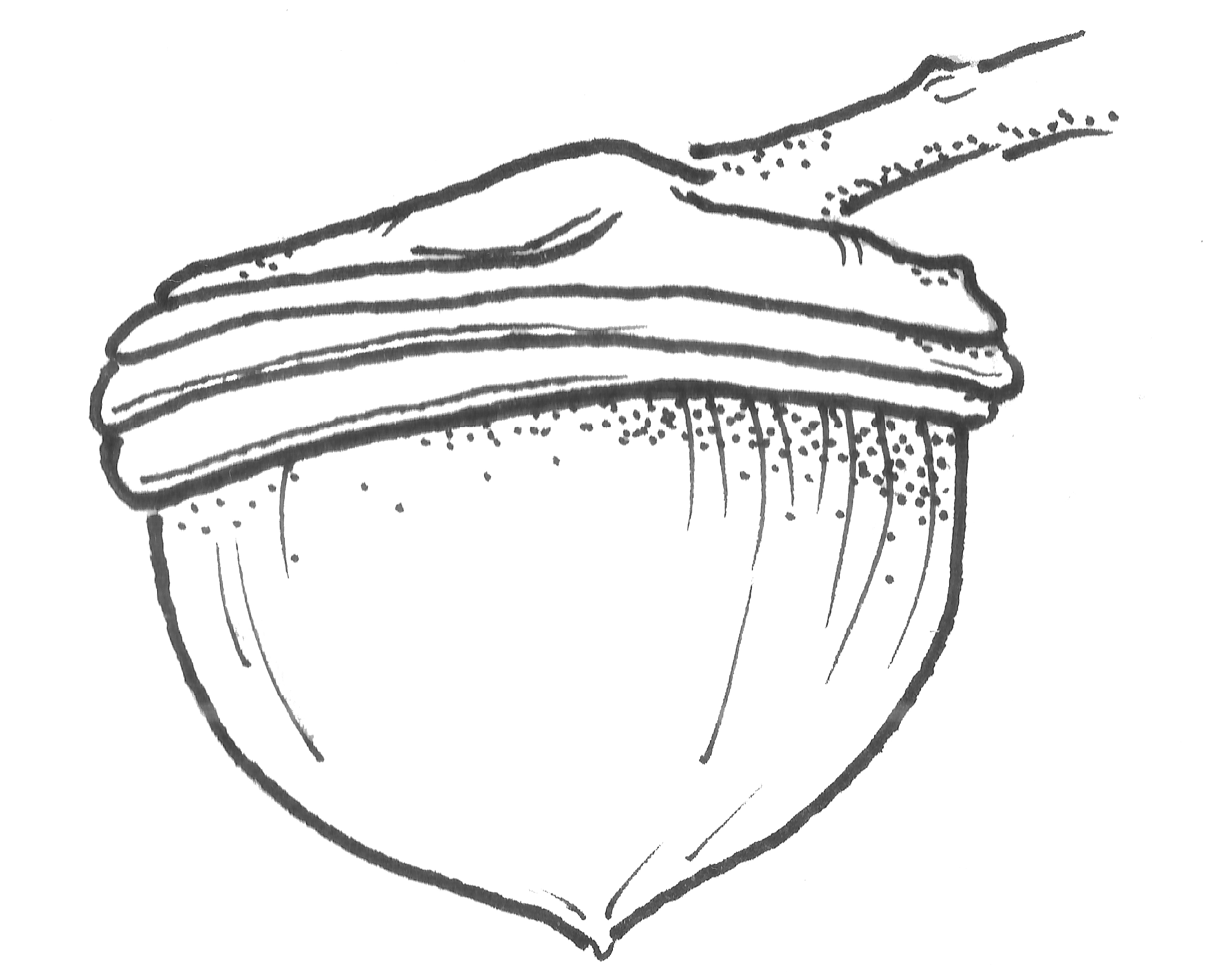

Lithocarpus lucidus (Shining Oak)

|

The cupule is cup to saucer shaped, covering less than half the fruit, the lamellae are dense and distinct set in 8–11 lines. Most of the depressed ovoid glabrous shining fruit is exserted with a rounded base and rounded apex. |

Conservation status: An endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus lucidus found on well drained soils in primary and lower montane forests. It occurs locally in Nee Soon Swamp Forest and the Upper Seletar Reservoir and Upper Pierce Reservoir areas.The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species is named for its shiny fruit. |

||||

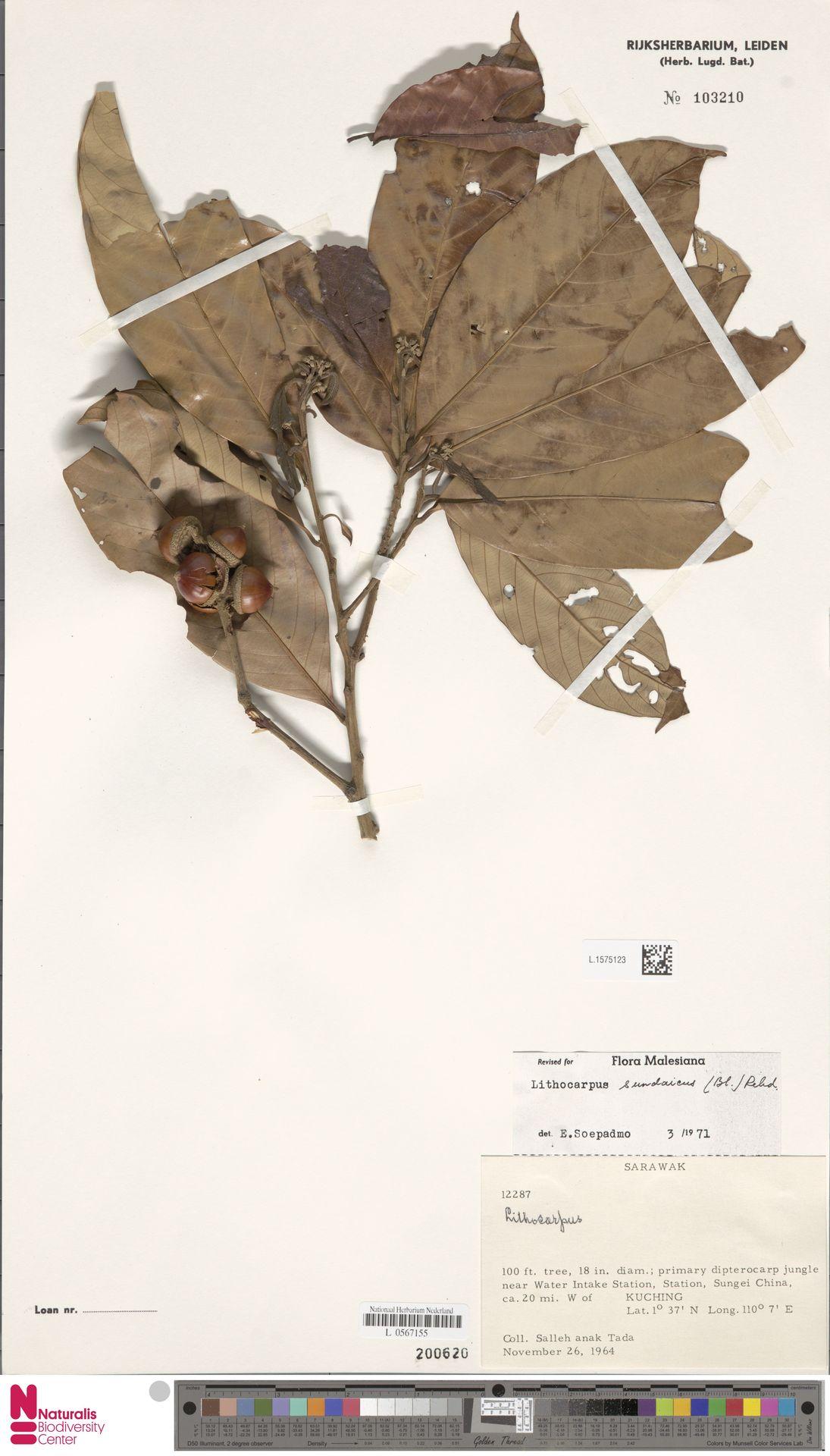

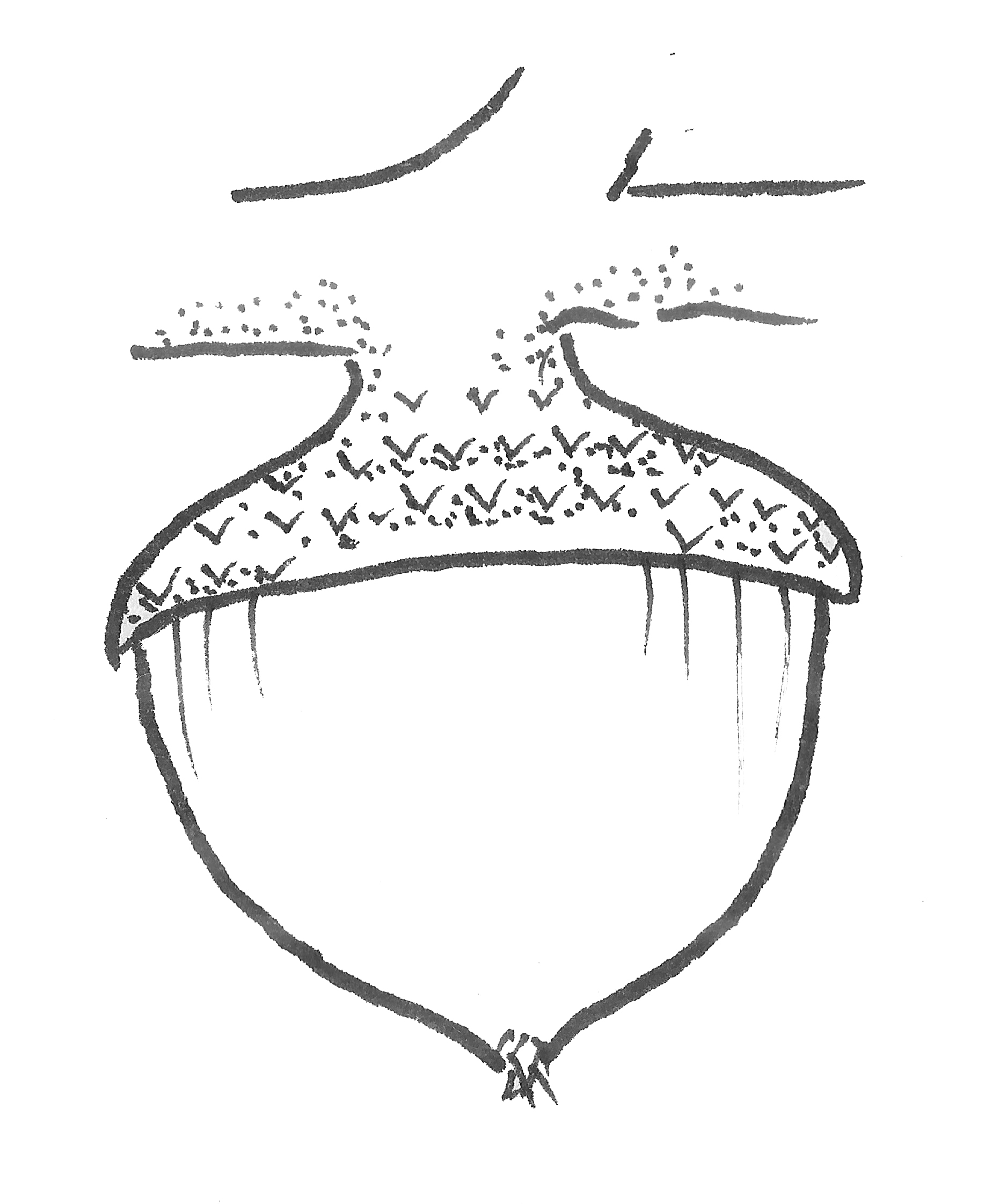

Lithocarpus sundacius (Sunda Oak)

|

The cupule is saucer shaped, densely hairy, with distinct scaly appendages set in regular lines. Most of the depressed ovoid glabrous shining fruit is exserted and has a hairy apex. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus sundacius is found on well drained soils in primary and lower montane forests.The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species is named for its occurrence on the Sunda Islands. |

||||

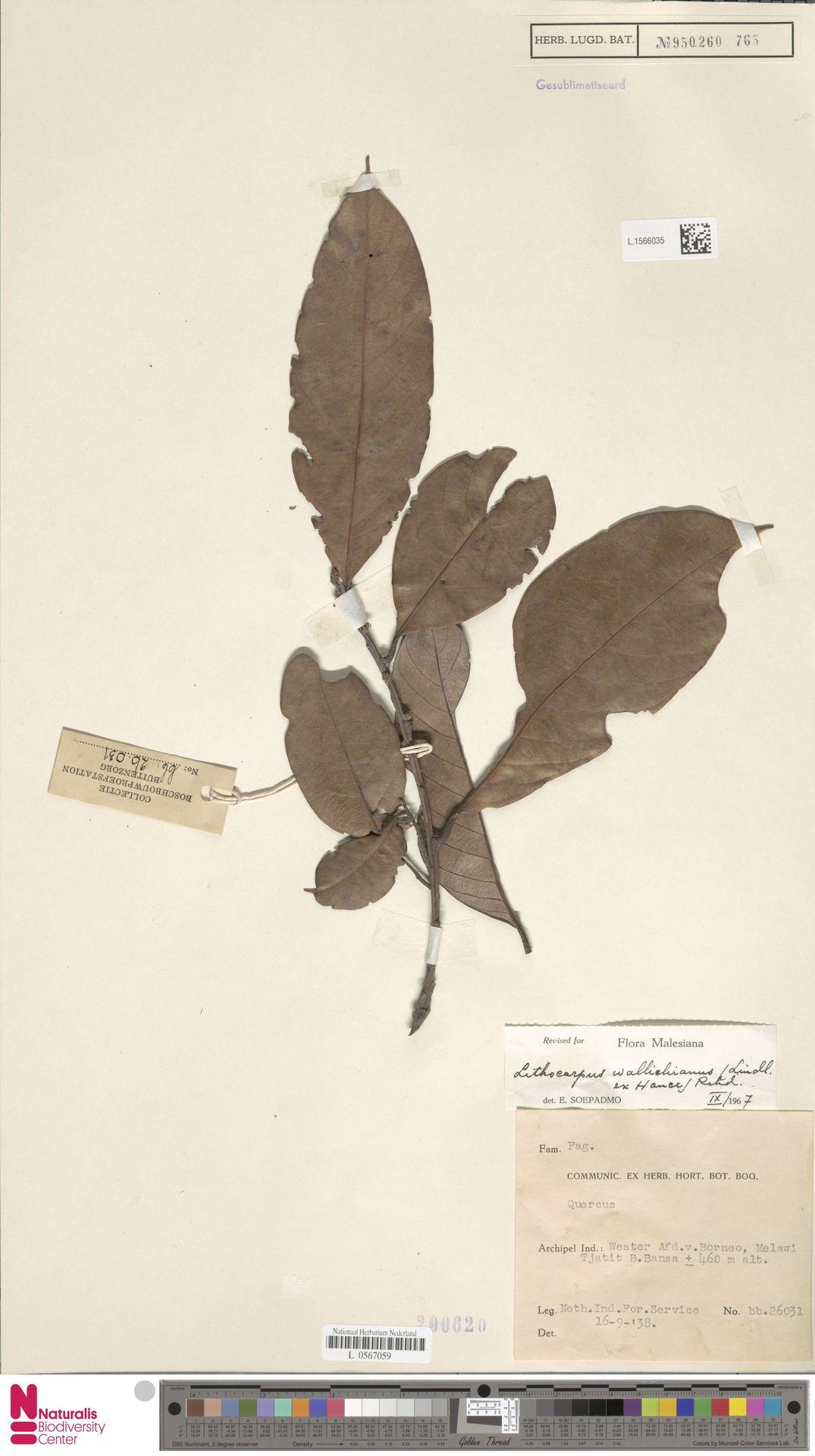

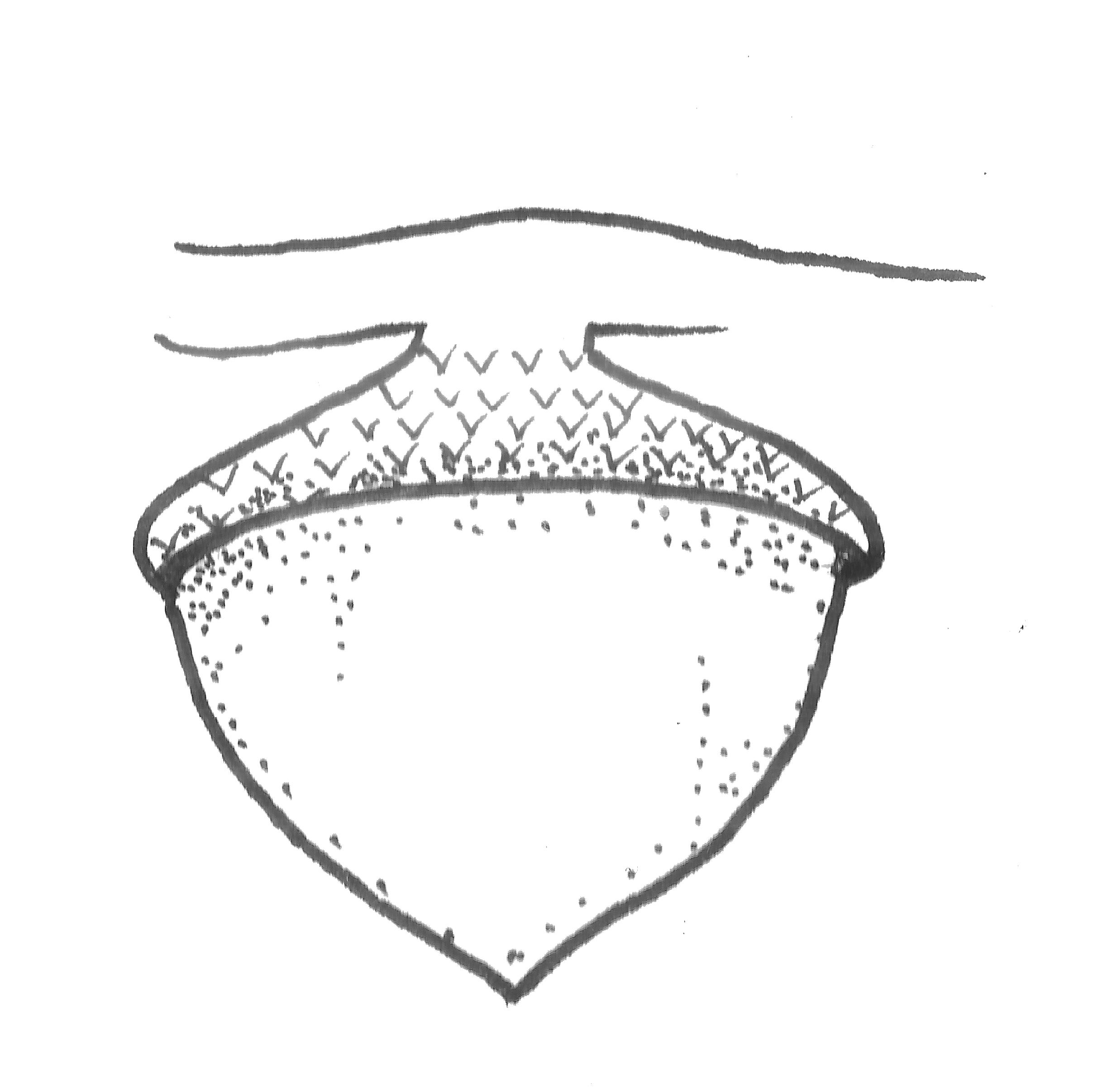

Lithocarpus wallichianus (Wallich's Oak)

|

The cupule is saucer shaped, densely hairy, with distinct scaly appendages set in irregular lines. Most of the ovoid fruit is exserted and is covered with simple hairs. |

Conservation status: A critically endangered, native tree. Local distribution: Lithocarpus wallichianus is found on well drained soils in hilly forests.The tree is cultivated in Singapore. Interesting Note: The species closely resembles the Common Oak (L. sundacius) especially the fruits, but has hairy twigs, larger leaves and longer fruit spikes with many acorns on them. |

What is it called again?

Taxonomy

Kingdom: PlantaeOrder: Fagales

Family: Fagaceae

Genus: Lithocarpus

Species: Lithocarpus elegans

Fagaceae

Though the Fagaceae dominate in temperate forests, the center of diversity is in Southeast Asia. Lithocarpus in particular are restricted to Asia and no species are known to exist in the Northern hemisphere.By Soepadmo’s admission the classification of Fagaceae species is based largely on gross morphological attributes, in particular the taxonomic limits are based on fruit and floral characteristics such as pollination syndrome and number of cupule valves.. Some systematists have proposed splitting the family into two distinct ones, or to split a few genera such as Quercus and Trigonobalanus into smaller genera. Even at the subfamily level, proposals have been made to rearrange the genera into different subfamilies and tribes. These changes are not yet widely accepted and for the most part the classification prescribed by Kubitzki (1993) is still used [6].

The family Fagaceae currently includes nine genera— Fagus, Castanea , Castanopsis, Chrysolepis, Colombobalanus, Formanodendron, Lithocarpus, Quercus, and Trigonobalanus [25].

Lithocarpus

In the past, there has been disagreement among botanists regarding whether the genera Lithocarpus and Quercus are sufficiently different and on whether Lithocarpus should be subdivided into at least 2 or 3 smaller genera [5].Lithocarpus was divided by Oersted (1867) into Cyclobalanus and Pasania. Similarly, Schwarz (1936) preferred to split the genus into three, Lithocarpus, Cyclobalanus, and Pasania. Oersted and Schwarz cited distinct cupule characteristics as a means of distinction for the smaller genera they recognized. Soepadmo indicates that generic distinction on the basis of one character is “always unsatisfactory”. Similarly in the case of Lithocarpus he argues that a narrow generic limit is invalid because there are many species in which cupule morphology is unclear. He also raises issue with the fact that there is general “uniformity in floral structure, pollen morphology, wood anatomy, and floral biology” for the Lithocarpus genus. Any one character is therefore not sufficient for distinction smaller genera. Soepadmo’s recommendation is that the “narrow generic concept be rejected” [5].

Soepadmo's position is in line with some past authors. Prantl (1889), placed all species in a single genus Pasania. Koidzumi (1916), likewise agreed to include all species in one genus, but under the name Synaedrys. Rehder & Wilson in 1916 restored Lithocarpus as the correct name for the genus [5].

Nomenclature

|

| Tangible elegance. (Photo by Reuben Lim) |

Scientific name: Lithocarpus elegansThe genus name 'Lithocarpus' is derived from the Greek 'lithos' for stone and 'carpos' meaning fruit, in reference to the hard acorns. The specific epithet 'elegans' is Latin for elegant, referring to the elegant acorns and cupule.

Author citation: Lithocarpus elegans (Blume) Hatus ex. SoepadmoThis author citation is complex and reflects how the species has been classified over the years. In the parenthesis is the name of the first author, C. L. Blume, who had assigned the specific epithet in a different genus (Quercus). It was then moved to the present genus (Lithocarpus) by the revising author S. Hatusima. The 'ex.' in the citation denotes that the subsequent author E. Soepadmo provided the validating description for the species.

Vernacular names: The tree is known by different vernacular names in different regions. In Singapore it is also known as Spike oak, Mempening, Empening or Berangan.

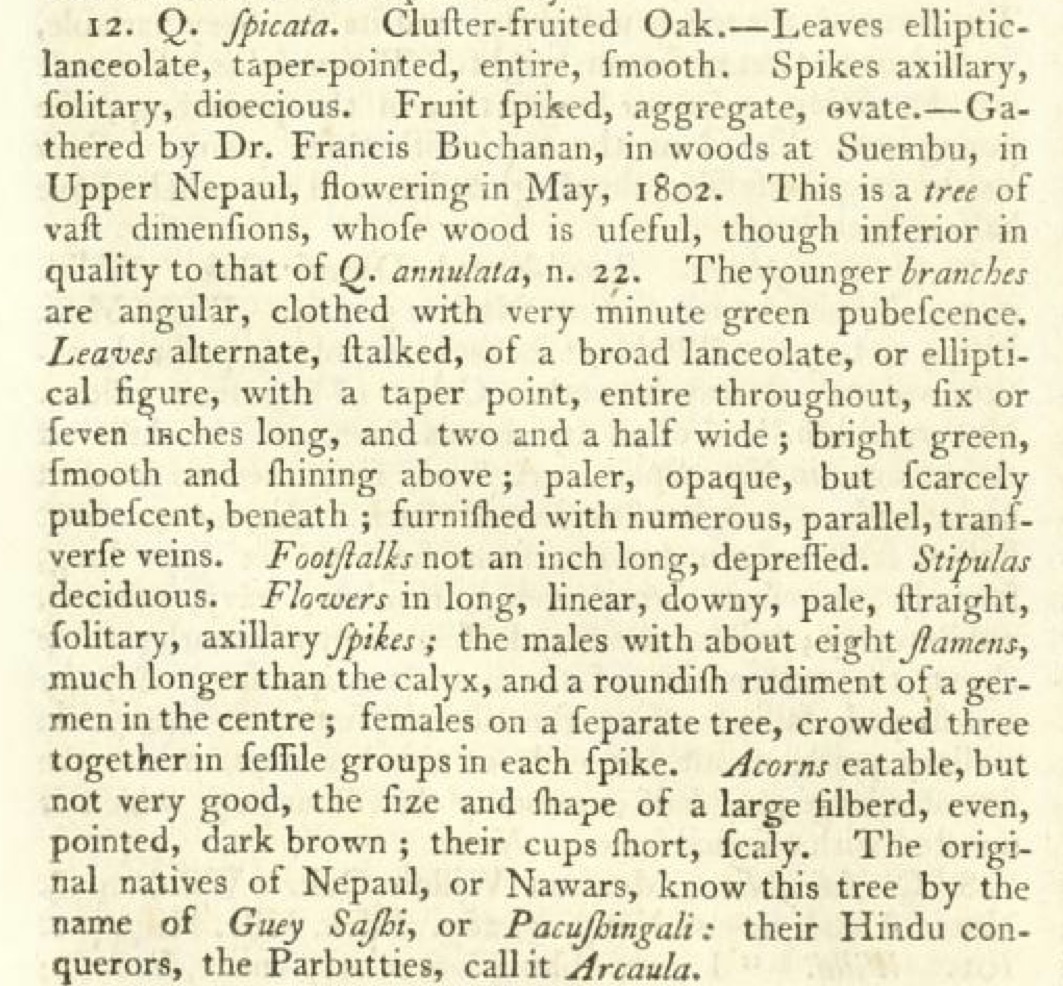

Protologue

The first valid published material associated with a scientific name, including diagnosis, description and illustrations constitutes the protologue. |

| First description of Quercus Spicata by Smith in the Cyclopaedia (1809). (Fair Use) |

On an unrelated but interesting note, in the protologue material on this species the long 's' (ſ) is used in the publication. This is similar in appearance to the minuscule 'f'. Which is why to the modern reader the description may seem 'ſtrange'.

This plant was first described as Quercus spicata by Smith in the Cyclopaedia (1809). This was the first of many names attributed to the this widely distributed and highly variable tree (See Synonyms). The species has been moved back and forth across genera. In the past, over seven varieties of the tree have been distinguished and some have even been recognised as distinct species. It was only in 1970 that Soepadmo concluded that none of the varieties deserved to be regarded as a separate species. He described Lithocarpus elegans as the most primitive of the genus and argued that the variations in morphology of the plant are primarily due to growth in different habitats and that in the past poor characters had been used to delimit the species. He instead suggested that the Lithocarpus elegans species be recognised by the "glabrous, pale to dark chocolate brown leaves, glossy on both sides and by the cupules which are always squamous and set in dichasial clusters of 3–10" [4].

Based on his treatment of the species L. elegans and the genus Lithocarpus it could be argued that Soepadmo ascribes to a relatively broad species concept.

The dramatic variation in the species is apparent in the images below, all of which are specimens from Peninsular Malaysia (accessed at SING) and have been determined as Lithocarpus elegans by species author Soepadmo.

|

| There is distinct variation in cupule and leaf size and shape. Specimens Poore 1267, Kasim 1476, Hothum 19803, Henderson 29732 at SING. Photos by Srishti Arora |

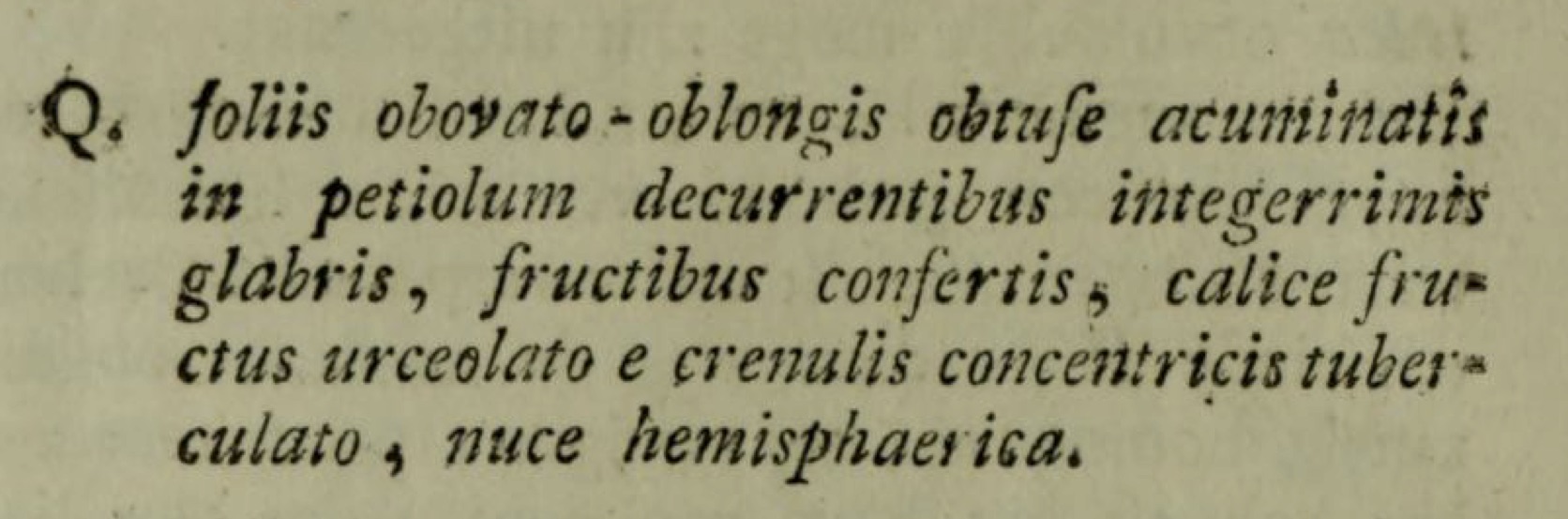

Basionym

The term basionym refers to the original name on which the present name attributed to the species is based. For Lithocarpus elegans, the basionym is Quercus elegans Blume. |

| Description of Quercus elegans by CL Blume, published in Verh. Batav. Genootsch. Kunst. ix. (1825) 208. (Fair Use) |

A rough translation of the latin description — The leaves are ovate-oblong, bluntly pointed with entire margin, smooth petiole, dense fruit with a hemispherical nut.

Synonyms

Synonyms are names that have been rejected by a particular author or authors. A synonym may be rejected for either of two reasons: (1) because it does not comply with the rules of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN); or (2) because a particular author rejects the classification associated with the synonym [23]. This is a selection of synonyms of L. elegans in Malesia. However there are even more synonyms, the full list can be found in Soepadmo's Florae Malesianae Praecursores XLIX (1970).Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl. 1809) Smith in Rees, Cyclop. (1814) 12; Q. racemosa (non Lam. 1783) Jack, Mal. Misc. 2 (1822) 86; Q. arcaula Hamilt. ex G. Don var. racemosa (Jack) Blume l.c. (1850) 290; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. racemosa (Jack) Miq., Ann. Mus. Lugd.-Bat 1 (1863) 106; Q. depressa Blume l.c. (1823) 209, t. 1; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. depressa (Blume) King, Ann. Roy. Bot. Gard. Calc. 2 (1889) 48, t. 43; Q. glaberrima Blume l.c. (1823) 210, t. 2; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. glaberrima (Blume) Miq. l.c. (1856) 848; L. spicata (Smith) Rehder var. glaberrima (Blume) A. Camus l.c. (1949) 103, t. 482; L. spicata (Smith) Rehder var. elegans (Blume) A. Camus l.c. (1949) 102, t. 481; Q. placentaria Blume, l.c. (1825) 518; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. placentaria (Blume) Schottky l.c. (1912) 664; Q. grandifolius D. Don in Lamb., Gen. Pin. 2 (1824) 27, t. 8; L. grandifolius (D. Don) S.N. Biswas, Bull. Bot. Surv. India 10 (1968) 258; P. spicata (Smith) Oerst. var. placentaria (Blume) Oerst. l.c. (1867) 83; Pasania spicata (Smith) Oerst. var. placentaria (Blume) Schottky l.c. (1912) 664; L. spicata (Smith) Rehder var. placentaria (Blume) Rehder l.c. (1929) 133; Q. glomerata Roxb., Fl. Ind. 3 (1832) 640; P. glomerata (Roxb.) Oerst. l.c. (1891) 379; Q. anceps Korth. l.c. (1844) 204; Q. microcalyx Korth. l.c. (1844) 206; Q. arcaula Hamilt. ex G. Don var. microcalyx (Korth.) Blume l.c. (1850) 290; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. microcalyx (Korth.) Miq. l.c. (1856) 848; P. spicata (Smith) Oerst. var. microcalyx (Korth.) Gamble l.c. (1915) 421; L. microcalyx (Korth.) A. Camus l.c. (1945) 83; Q. pyrifolia Blume l.c. (1850) 304; Q. sphacelata Blume l.c. (1850) 304; Q. gracilipes Miq., Fl. Ned. Ind. 4, Suppl. (1861) 347; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. gracilipes (Miq.) Miq. l.c. (1863) 106; P. spicata (Smith) Oerst. var. gracilipes (Miq.) Schottky l.c. (1912) 664; L. spicata (Smith) Rehder var. gracilipes (Korth.) Rehder l.c. (1919) 131; Q. spicata (non Humb. & Bonpl.) Smith var. latifolia Scheff. l.c. (1870) 359; Q. rhioensis Hance l.c. 198; L. rhioensis (Hance ) A. Camus l.c. (1932) 40.

Type specimen

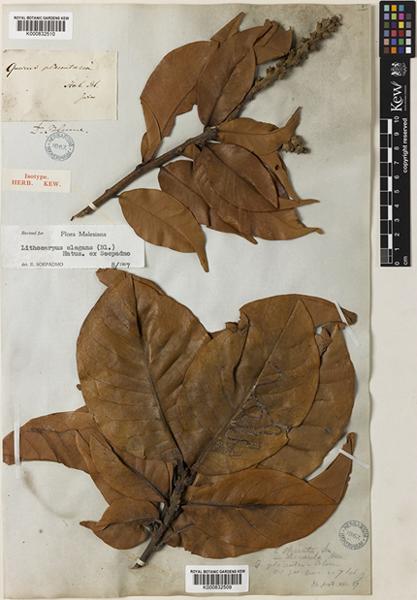

The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) states that scientific names need to be associated with a physical entity known as a nomenclatural type or simply type. The nomenclatural type is usually a herbarium sheet specimen; other specimens of the species are compared with the type specimens [20].Types of types

The holotype is the specimen designated in the original publication of the species on which the name is based. The Holotype for the species collected by Blume from Bantam Residency in Java is housed at the Leiden branch of the National Herbarium of the Netherlands (L).

An isotype is a duplicate specimen of the holotype collected at the same time and from the same population. It is recommended that isotypes be designated in the publication of a new name as they are reliable duplicates. Isotypes of L. elegans are available at the Herbarium at Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (K), the herbarium of Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (P) and at the Cambridge University Herbarium (CGE).

Other types of types include [20]:

Lectotype: A specimen from the original publication that shall serve as the type if no holotype is designated at the time of publication.

Neotype: A specimen that is not included in the original material that shall serve as the type if all original material is missing.

Syntype: Multiple specimens all designated as types, or a specimen cited in the absence of a holotype.

Paratype: All specimens not designated as holotypes, isotype or syntype but cited in the original material. Soepadmo has cited several specimens in his publication for L. elegans.

Epitype: A specimen designated to serve as the type if the holotype, lectotype or neotype is ambiguous,

|

| Isotype of Lithocarpus elegans at K. Photo from JSTOR's Global Plants Database. |

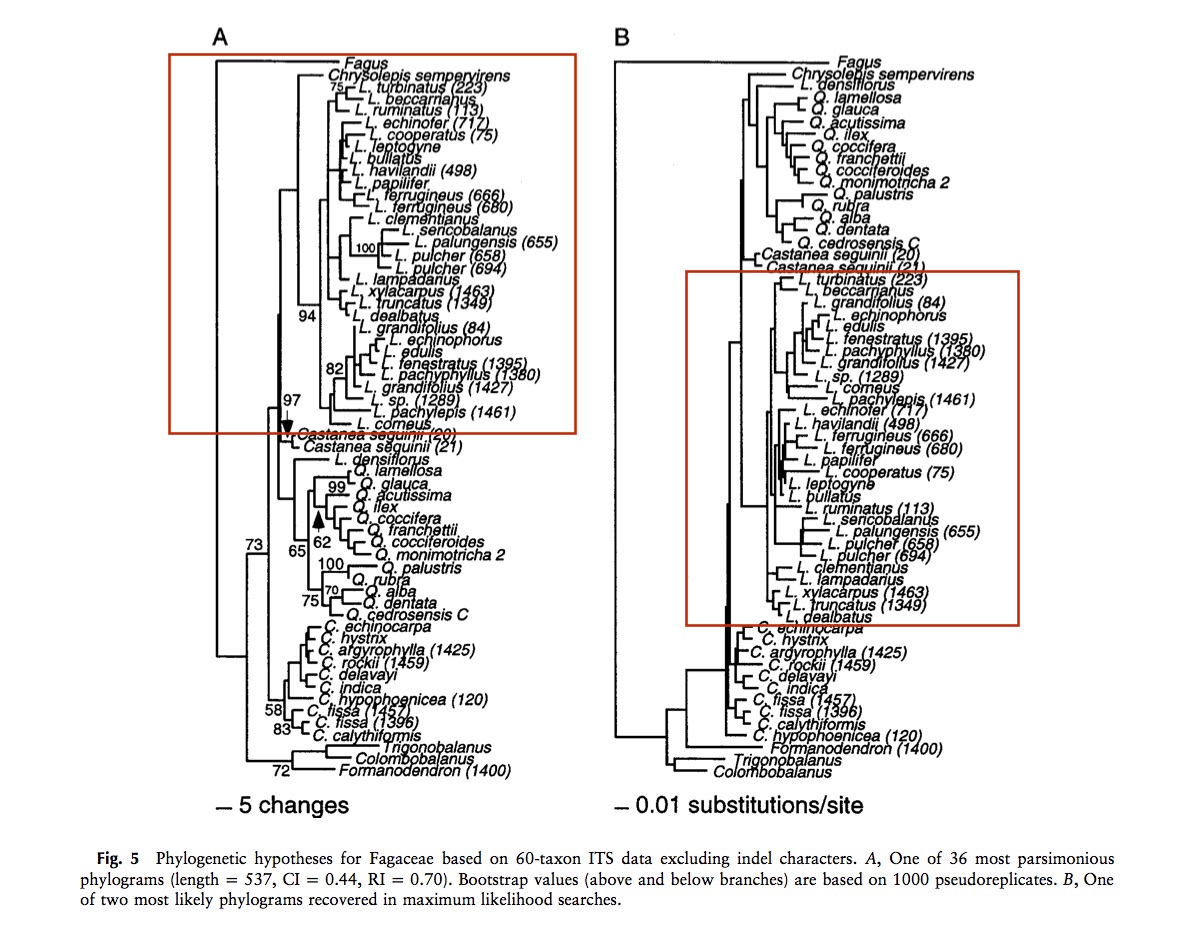

Phylogeny

There have not been many phylogenetic studies of the genus Lithocarpus, and no published accounts could be found for L. elegans. The most comprehensive analyses available are the ‘Systematics of Fagaceae‘ by Manos et al (in which the authors used DNA sequence data to reconstruct phylogeny, assess systematic relationships, and explore alternative patterns of morphological specialization) and ‘Morphological and molecular diversity in Lithocarpus of Mount Kinabalu’ by Cannon et al [25] [26]. |

| From Manos et al (2001) Systematics of Fagaceae - Phylogenetic tests of reproductive trait evolution. (Adapted by Srishti Arora) |

For the most part, taxonomic classification of Lithocarpus has been stable, forming the most strongly supported group (bootstrap analysis) in the Fagaceae family and the genus appears to be monophyletic. In the genus, the species are divided into distinct sections based on fruit morphology. Manos et al’s results indicate that several sub-clades in Lithocarpus corresponded to the previously delimited groups [26][27].

It is interesting to note that in general the species of Lithocarpus tend not be widespread making L. elegans and L. grandifolius notable exceptions. Unfortunately, this aspect of L. elegans phylogeography specifically has not been explored. It has been indicated that initially the ancestral group of Lithocarpus was widespread across South and Southeast Asia allowing the ancestral haplotype to reach either end of the subcontinent without significant alteration. Subsequently, the widespread population became fragmented and experienced an extreme bottleneck in central Sundaland. This bottleneck together with fragmentation caused the Bornean lineage to undergo significant genetic drift and to diversify in isolation, which may explain why the greatest diversity of haplotypes is found in Borneo and the relatively low frequency of occurrence of the ancestral haplotype. It is safe to say however that species boundaries of Lithocarpus are yet to be fully understood and further phylogenetic analyses are likely to reveal this [25] [26].

All photos are used with permission from photographers unless otherwise stated. Credit is attributed to photographers in the picture caption.

For the composite image at the top of the page: The photos were taken by Srishti Arora, Louise Neo and Reuben Lim (From left to right).

References

| [1] Cannon CH & Manos PS (2001) The Bornean Lithocarpus Bl. section Synaedrys (Lindl.) Barnett (Fagaceae): its circumscription and description of a new species. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 133: 343–357. |

| [2] Corner EJH (1988) Wayside Trees of Malaya. The Malayan Nature Society, 1: 327–343. |

| [3] Julia S & Soepadmo E (1998) New Species and New record of Lithocarpus Blume (Fagaceae) from Sabah and Sarawak, Malaysia. Gardens' Bulletin Singapore, 50: 125–150. |

| [4] Soepadmo E (1972) Flora Malesiana. Wolters-Noordhoff Publishing, Groningen, The Netherlands, pp. 265–403. |

| [5] Soepadmo E (1970) Florae Malesianae Praecursores XLIX Malesian Species of Lithocarpus Bl. (Fagaceae). Reinwardtia, 8(1): 197–308. |

| [6] Soepadmo E, Julia S & Go R (1995) Fagaceae. In: Soepadmo E & Wong KM (ed.) Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak. Volume 1. Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM), Sabah Forestry Department, and Sarawak Forestry Department, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, pp. 1–166. |

| [7] Whitmore TC (1972) Tree Flora of Malaya A Manual for Foresters. Longman, Forest Research Institute, Kepong, 1: 198–209. |

| [8] Chong KY, Tan HTW & Corlett RT (2009) A CHECKLIST OF THE TOTAL VASCULAR PLANT FLORA OF SINGAPORE: Native, Naturalised and Cultivated Species. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore, pp. 56. |

| [9] Treuttel and Wurtz (1832) Plantae Asiaticae rariores, or, Descriptions and figures of a select number of unpublished East Indian Plants. London, pp. 40–41. (Accessed from the Biodiversity Heritage Library on 1 November 2017) |

| [10] Tan H (2012) Butterflies of Singapore. Version 1 December 2017. http://butterflycircle.blogspot.sg/2012_07_21_archive.html (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [11] Hickey M and King C (2000) The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms. Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–47 |

| [12] Colin Mills (2010) Lithocarpus elegans (Blume) Hatus ex. Soepadmo. Version 28 February 2010. http://hortuscamden.com/plants/view/lithocarpus-elegans-blume-hatus.-ex-soepadmo (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [13] National Parks Board (2013) Flora and Fauna Web:Lithocarpus elegans (Blume) Hatus ex. Soepadmo. https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/special-pages/plant-detail.aspx?id=2999 (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [14] Ken Fern (2014) Useful Tropical Plants Database: Lithocarpus elegans. http://tropical.theferns.info/viewtropical.php?id=Lithocarpus+elegans (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [15] Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown (1819) The cyclopaepedia; or, Universal dictionary of arts, sciences and literature. University of California Libraries, 29. (Accessed from the Biodiversity Heritage Library on 1 November 2017) |

| [16] Biodiversity Heritage Library (2017) Biodiversity Heritage Library. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [17] Bioportal (2017) Naturalis Biodiversity Centre. http://bioportal.naturalis.nl/?language=en&back (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [18] JSTOR (2017) Global Plants Database. http://plants.jstor.org/ (Accessed 1 December 2017) |

| [19] Nghiem LTP, Tan HTW and Corlett RT (2015) Invasive trees in Singapore: are they a threat to native forests? Tropical Conservation Science, 8(1): 201–214. |

| [20] Simpson MG (2006) Plant Nomenclature: Plant Systematics. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 501–517. |

| [21] Simpson MG (2006) Plant Nomenclature: Phylogenetic Systematics. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 17–51. |

| [22] Simpson MG (2006) Plant Nomenclature: Diversity and Classification of Flowering Plants: Eudicots. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 227–347. |

| [23] Simpson MG (2006) Plant Nomenclature: Resources in Plant Systematics. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 507. |

| [24] Cairn MF (2015) Shifting Cultivation and Environmental Change: Indigenous People, Agriculture and Forest Conservation. Routledge, pp.425–428. |

| [25] Manos PS et al (2001) Systematics of Fagaceae - Phylogenetic tests of reproductive trait evolution. International Journal of Plant sciences, 162(6): 1361–1379. |

| [26] Cannon HC and Manos PS (2003) Phylogeography of the southeast asian stone oaks Lithocarpus. Journal of Biogeography, 30: 211–226. |

| [27] Cannon HC (2001) Morphological and molecular diversity in Lithocarpus of Mount Kinabalu. Sabah Parks Nature Journal, 4: 45–69. |